Natasha Reid, The University of Queensland

State and federal minsters involved in the Forum on Food Regulation will tomorrow vote on whether or not to introduce mandatory alcohol pregnancy warning labels in Australia and New Zealand.

If approved, it will be an important step in reducing alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

At the same time, the public health response to this issue needs to go beyond warning labels.

Read more: Alcohol warning labels need to inform women of the true harms of drinking during pregnancy

Alcohol permeates Australian culture

Alcohol plays a key role in our social activities and celebrations. We also commonly drink alcohol to relax or cope with stress.

The Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education (FARE) found 20% of households reported buying more alcohol than usual during the COVID-19 pandemic. In these households, 70% of people reported drinking more than usual since COVID-19 began, and 32% were concerned about the amount of alcohol they or a loved one was drinking.

More broadly, new Australian Institute of Health and Welfare statistics show the number of people drinking at risky levels has remained stable since 2016, but is substantial.

In 2019, 3.5 million people (16.8%) consumed more than two drinks per day on average, and about 5.2 million people (one in four Australians) consumed more than four drinks in one occasion (defined as binge drinking) at least monthly.

Given the broad cultural acceptance of alcohol use in Australia, it’s hardly surprising alcohol is also consumed during pregnancy. What may surprise people, though, is Australia has some of the highest rates of alcohol use during pregnancy in the world: around 35.6%.

What’s the problem with drinking during pregnancy?

Alcohol use during pregnancy can have many unintended consequences, including miscarriage, stillbirth, preterm delivery, and foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). This disorder refers to a range of problems caused by foetal alcohol exposure, the effects of which can be lifelong.

Prenatal alcohol exposure has a dose-response effect, meaning higher rates of drinking increase the risk of these outcomes.

Read more: Health Check: what are the risks of drinking before you know you're pregnant?

But alcohol use in pregnancy doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It’s interlinked with individual, family, societal and cultural determinants, which set the stage for and perpetuate alcohol use during pregnancy.

Any perception alcohol use during pregnancy is only a woman’s issue or only a woman’s fault is inconsistent with the context we live in, and ultimately unhelpful in preventing alcohol use during pregnancy.

Research shows a wide range of environmental factors increase the risk of alcohol use during pregnancy and as a result, FASD. These include living in a culture that accepts heavy drinking, coming from a family of heavy drinkers, having a partner who is a heavy and frequent drinker, recreation that is centred around alcohol use, and having little or no awareness of FASD.

What would the label look like?

In Australia, we’ve had a voluntary pregnancy warning label scheme since 2011. But there’s been low uptake. A 2017 evaluation found only 47.8% of alcohol products featured a pregnancy health warning label.

Read more: Revised DrinkWise posters use clumsy language to dampen alcohol warnings

Meanwhile, public health experts and FASD advocates have expressed concern over the size, colour and visibility of current warning labels.

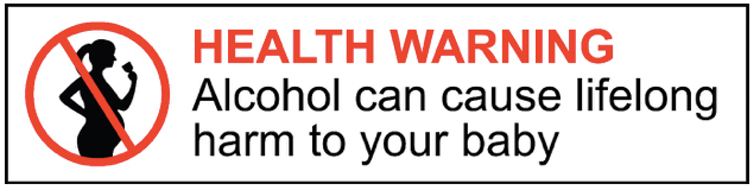

As a result, Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) has recommended a mandatory, consistent and highly visible label for all alcoholic beverages.

This would bring Australia into line with many other countries, including the United States, France and Mexico. The US has had mandatory pregnancy health warning labels on alcohol products since 1989.

Evidence shows the proposed label will be more effective than other options. The design features key colours (black, white and red) that increase attention to the warning, and the statement — “HEALTH WARNING: Alcohol can cause lifelong harm to your baby” — combines the best performing elements from consumer testing.

If the ministers vote to endorse the warning label proposed by FSANZ, there will be a two-year transition period for implementation of the labels.

But there’s more we should be doing

Making warning labels mandatory is a vital component in a comprehensive prevention approach. But warning labels alone won’t be enough to prevent alcohol use during pregnancy and FASD.

An international leader in the FASD prevention space, Nancy Poole, has developed a four-part framework outlining the range of interventions required to enable effective FASD prevention. These include:

-

broad public awareness and health promotion

-

conversations about alcohol use and related risks with people of reproductive age

-

specialised holistic support for pregnant women experiencing alcohol problems

-

postpartum support for new mothers and support for child assessment and development.

Importantly, these components are underpinned by supportive alcohol policy (for example, alcohol taxes and prices, restricting the number of alcohol outlets in particular geographical areas, and restricting alcohol marketing).

This model shows us that no single approach will be effective in preventing alcohol use during pregnancy and FASD. We need action at each of these levels.

But visible and mandatory pregnancy warning labels are an important step forward in our national prevention journey.![]()

Natasha Reid, Research Fellow, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.